Now that the Talladega circus is over, it’s time for the old grump to knock NASCAR’s longest track and argue for its replacement, right? Oh, OK . . . since you asked.

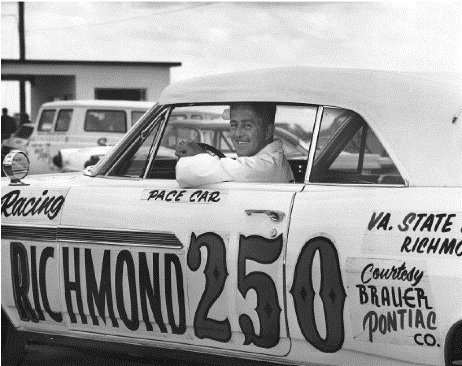

I mentioned recently that I celebrated a major anniversary earlier this month, 60 years since I attended my first race, the 1963 Richmond 250 at the Atlantic Rural Exposition fairgrounds, now home of Richmond Raceway. That race made me a lifelong fan.

But why? And how can I wax poetic about a race that finished with an average speed of 58.624 mph and a winner who led by a full lap, then refuse to watch Talladega, where speeds are more than three times what they were at Richmond, and a whole pack of cars comes roaring to the finish line, separated by a couple of seconds?

(And while you’re at it, Frank, explain why that was such a great race if only 15,000 people were there, as opposed to a much larger in-person Talladega crowd, plus a national television audience. AND, none of the Talladega crowd left with their off-white jackets – and pink lung linings – covered with black tire dust.)

Challenge accepted; I’ll try.

Let’s start with the speed. I’ve never gone 180 mph. About 50 years ago, a guy who said he owned six shares of Charlotte Motor Speedway stock – entitling him to drive on that track – took me for three or four laps around the speedway with the speedometer buried on his Plymouth Roadrunner. That’s the fastest I’ve even been in a car.

However, when I was a young driver, still proving that driving and surviving were two words I could string together, there were still a lot of dirt roads in rural areas, and they tended to encourage testing that drive/survive equation.

For some reason, I recall coastal roads in Virginia’s Northern Neck region (near the Chesapeake Bay and Potomac River), where it was customary to supplement the dirt surface with crushed oyster shells. That’s not a combination conducive to traction, and to teenaged boys, the lack of traction was an asset, not a liability. The proximity to water was ironic, given the amount of fishtailing we did.

I also particularly remember the back road from U.S. 360 to Southside Speedway in Richmond. It ran straight into the parking lot, and it was dirt/gravel, made even more fun in the summer when they spread oil on it to keep the dust down. It was lined with trees, so fishtailing could have gotten hazardous, but we roared out to the highway after the races every Friday night and lived. I’ll leave it to the theologians to decide whether that means God is merciful, tolerant, or just has a sense of humor.

The point is, while I couldn’t identify with high speeds at Talladega (and remember that Richard Brickhouse’s winged Dodge topped 196 mph nearly 54 years ago), I could easily identify with sliding around the Richmond fairgrounds track at something in excess of 60. My brain could transport itself into one of those 25 cars on that April Sunday and make me a racer. As a result, every bit of action was exciting to my core.

That was a model, by the way, that was slow to change. The first Strictly Stock/Grand National/Cup race ever run, at Charlotte in 1949, had about same speeds as Richmond 14 years later. Daytona’s beach-road course was fastest, but only with an average speed of about 80, and that was with a couple of miles of straight, paved highway in play. North Wilkesboro (then dirt) was slowest of the tracks for which we have records, with a qualifying speed of 57.569 and race average of 53.364.

Nowadays, Martinsville, the slowest oval on the circuit, has qualifying speeds of nearly 100. I can sort-of identify with that, but the youthful experience of raising hell on dirt roads still has the more meaningful spot in my memory.

So back to racing: What occurs to me after this ramble is that identifying with the car speeds and other racing conditions has changed in the same way as a lot of the other details of the sport, and those changes are at the heart of a lot of the disaffection among older fans (who still outnumber the younger ones by a considerable amount, I believe).

Big Bill France’s “strictly stock” concept didn’t last that long and has been changing pretty much throughout the past 75 years, but for whatever reason, fans seemed to put up with it through the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, even as NASCAR permanently left the identification with “stock cars.” The tipping point, though, came with the Car of Tomorrow, about 20 years, and accelerated as NASCAR moved from cars actually produced by the manufacturers to cars designed and – for all practical purposes – built by NASCAR or its contractors.

Along with that went the micro-management of rules and the mindset that “cheating” was a capital offense, not something you tried to get away with when you thought you could, accepting a slap on the wrist when you couldn’t.

Then there are the driver/team changes. At that 1963 Richmond race, the 25 cars came from 22 different teams, only Cotton Owens, Petty Enterprises, and Ray Fox fielded two-car teams. (It looked like Holman-Moody had a pair of cars on hand for Fireball Roberts and Fred Lorenzen, but the latter was driving a non-HM deal car.)

NO CHARTERS! No reduced qualifying options or compensation. No corporate welfare. Go or go home.

I always liked Richmonder Larry Manning’s story. In the spring of ’63, he went to North Carolina to buy a well-used ’62 Chevy Grand National, and one the way home realized that a race was being held at Hillsboro’s Occoneechee/Orange County Speedway. Without ever having taken the car into his own garage, Manning stopped at Hillsboro (the name officially changed to Hillsborough two years later) and raced it. He was nowhere near competitive, but thanks to attrition, he finished 8th.

Try wandering into the pre-race Cup garage today and see what happens.

The cars not only were relatively stock, but they were fragile. Only 11 of the 25 starters finished that April day in ’63, and most were miles and miles behind at the finish. By today’s standards, fans might call it a lousy race.

I didn’t. The battles between Joe Weatherly and Junior Johnson were riveting, as were briefer and less decisive ones involving the likes of David Pearson, Jim Paschal, and others. Watching amateur pit crews change tires or repair damaged cars was entertaining.

At the end of the race, you could walk around the track and pick up small pieces of race car that had fallen off and been imbedded in the clay. I still have a gas cap somewhere.

To me, it was a more authentic motorsports experience. Not as much spectacle – at least other than the “parade of visiting pace cars” that (along with Linda Vaughan riding around on the plywood Pure Firebird) constituted pre-race ceremonies in those days.

By the time the race started, I was probably eating a corn dog (“Pronto Pup” as fresh-battered-fried-and-sold by Richmond Concessionaire) or sausage/pepper/onion sub, and taking pictures with my little Brownie camera like I’d be able to see any details in the result.

By the time it was over, I was covered in that black dust, and I was happy.

Today it’s about the show, the entertainment. Then, it was about auto racing the sport. To some, Talladega still represents that sport, but not to me. Being able to identify with what’s going on remains important to me, which is why I spend most of my race days today with a group of hobbyist sprint car drivers who love what they do and don’t earn enough money at it to pay a Cup team’s pit pass bill.

That’s why I’m grateful for my Richmond memories.

Frank’s Loose Lug Nuts

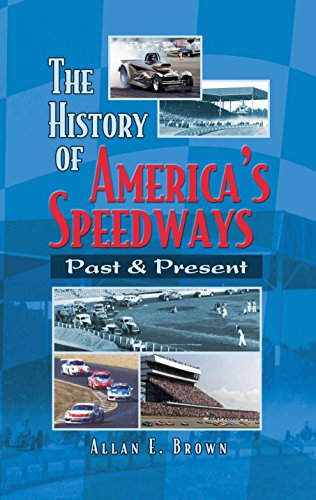

This sport’s history means a lot to me, which is why I mourn the passing of Allan E. Brown, author of the book, History of America’s Speedways, Past and Present.

Brown initially was best known as editor/publisher of the National Speedway Directory, the Bible for race fans looking for different tracks. I always felt I wasn’t a real fan because I only bought a new copy every other year. Some people considered the start of the new season to be the arrival of a postcard announcing the new directory edition was available.

It was the “History” book, though, that will carry Brown’s legacy. Somebody really, REALLY tried to capture the entire history of the sport by identifying as many current and former tracks as possible. Of course, today lots of people use the web to search for obscure tracks from long ago, but Brown laid the groundwork, and his book remains a classic. I’m proud to say I was a tiny contributor to one edition.

Some people don’t devote themselves to making as much money off racing as possible; they just do what they do because they love it. Thank you, Allen Brown, for being one of the greatest of those.

A Final Note – The PA Sprint Series got rained out again Saturday night (we’re two-for-five now), and Talladega certainly didn’t fill my need for a substitute. For me, it’s a joke that doesn’t make me laugh. Fortunately, we have another IMCA/RaceSaver sprint car race next Saturday, running at Port Royal Speedway along with 410 sprints and 360 USAC East Coast Wingless sprinters. Should be awesome.

(PHOTO CREDITS – On the “cover,” the dirt track photo is from the NASCAR Hall of Fame, and the Talladega shot is from Motorsport.com. The Richmond pace car being driven by Paul Sawyer is credited to various sources including the NASCAR Hall of Fame, but the copy I copied was posted to Racers Reunion by Dave Fulton. The sliding car on a dirt road was from Freepic. The ’65 Chevy stock car (Roy Mayne’s ride) was from GM Authority, and the Car of Tomorrow was from Wired. The Larry Manning photo has the credits printed right on it. The Allen E. Brown photo was from the Grand Rapids (Mich.) Press, where it appeared with his obituary. The book cover is from ABE Books.

Frank Buhrman

I wish everybody’s 1st race could have been a 1960s outing at the Richmond dirt track. Sitting in those 4th turn bleachers and feeling them shake when the green flew was an experience. Fans who never saw full sized autos racing on a dirt track missed a real treat. Thanks for turning the clock bsck, Frank.

Never got up to any of the states like VA, N.C. or S.C. Sure wish I could have, but then near Daytona was a great place to be in those days.

We all love turning back the clock, and passing those memories and history along, don’t we?

We know which memories are worth preserving.

Frank, what a great story and the writing of it!

Sometimes people say we want to go back and live that life again, but all we are doing is passing on history through our memories. I am grateful we can do that. You add a lot to that history. Thank you.

Ever so often I got wandering down my memory lane of NASCAR and the beginnings I experienced. I can remember walking on the beach at Daytona and retracing some of the track. I never attended one of those races but I knew someone who had won one of them and he became my friend and mentor. There was so much to learn. It is because of people like him that fans like you and I, plus many others, love pure, true stock car racing as much as we do.

Thank you again!

When I hear other peoples’ stories, Vivian, I’m regretful that I didn’t pursue more opportunities for memories like these, but I’m certainly happy with the ones I’ve got.

Unfortunately, as with most sports involving technology, time creates advances and upgrades. I for one, DO wished that manufacturers still built the cars and that individual teams were responsible for building motors/chassis/bodywork, etc. That area is one that NASCAR has really lost out in and one reason I believe that NASCAR has lost a generation, maybe two, of young fans. Because out in the real world, there IS a young generation of gearheads that just cannot identify with spec cars and everyone running the same thing with little room for “changes.” On the converse, today’s car looks MUCH more like the production model cars currently on the street, in dimension and shape. I do believe NASCAR needs to go back to the things that made the sport so successful in the 80s and 90s-such as a full season champion, etc. However, I will still watch, because I bleed NASCAR blood.

Your last remark about bleeding NASCAR blood, made me think of an old Chevy Dealer I worked for. Because I was always talking and watching racing, he told me that I have gas in my blood. I truly believe there are many of us that are like that. I just wish I was young enough to attend in person still. NASCAR has changed a lot since they started on that dirt back in Daytona!!!